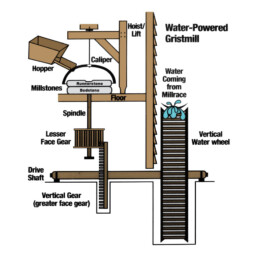

Parts of a Water Mill

Sluice gates controlled the flow of water going to the wheels. The gear mechanism that caused the grinding stones to turn varied greatly. Mostly there was a gear attached to a shaft turned by the water wheel. The diagram to your left shows a “undershot” arrangement, which is similar to ours. This image shows an average grist mill’s operation.

The grinding stones were mostly granite and purchased from afar. The best ones came from Europe at great expense, but could last for a hundred years. Each stone weighed between half a ton to two tons, and had to be lifted each year to be refaced. The water grooves needed to be carefully repaired so that grains could be ground to the correct size. Uneven runner stones would also damage the underlying or “bed” stone.

So the stones were arranged so that the miller could raise them up or let them down in order to control the fineness of the product. Roughly cracked corn may have been required for animal feed while fine meal was used for baking. And intermediate corn particles were used for making grits.

The millstones themselves turned at around 120 rpm. They are laid one on top of the other. The bottom stone is called the “bed” and is fixed to the floor. While the top stone (the “runner”) is mounted on a separate spindle, driven by the main shaft. The distance between the stones can be varied to the product grade of flour required; moving stones closer together produces finer flour.

A (very brief) history of water mills

Grist mills turned by water have existed for centuries, some as early as 71 B.C.E in Ancient Turkey. The photo seen here shows a reproduction of a typical grain mill in Ancient Rome. Although the terms “gristmill” or “corn mill” can refer to any mill that grinds grain, the terms were used historically for a local mill where farmers brought their own grain and received back ground meal or flour, minus a percentage called the “miller’s toll”. Millers had a pretty fair living by charging a portion of the grain as pay for their labours. For example Cuthbert Grant who built the original mill took 10% of the grain as payment for his services alone in the 19th Century.

Types of Water Mills

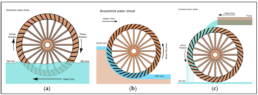

The Undershot type (bottom left) is what our mill has and looks similar to a paddle wheel. The wheel is simply propelled by the flowing water pushing on its blades.

Dressing a millstone ...

The surface of a millstone is divided by deep grooves called “furrows” into separate flat areas called “lands”. Spreading away from the furrows are smaller grooves called “feathering” or “cracking”. The grooves provide a cutting edge and help to channel the ground flour out from the stones.

The furrows and lands are arranged in repeating patterns called “harps”. A typical millstone will have six, eight, or ten harps. The pattern of the harps is repeated on the face of each individual stone, and when they are laid face-to-face, the patterns mesh in a kind of “scissor” motion creating the cutting or grinding function of the stones. When in regular use, stones need to be dressed periodically, that is, re-cut to keep the cutting surfaces sharp.

Millstones need also be evenly balanced and achieving the correct separation of the stones is crucial to producing good flour. The experienced miller will be able to adjust their separation very accurately.

Grant’s Old Mill is located on Treaty 1 territory, the traditional lands of the Anishinaabe, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dene, and Dakota Peoples, and the homeland of the Métis Nation.

© 2026 Grant's Old Mill Museum. All rights reserved