Grist Milling 101

Gristmills turned by water have been around for many centuries, some as early as 19 BC. Although the terms “gristmill” or “corn mill” can refer to any mill that grinds grain, the terms were used historically for a local mill where farmers brought their own grain and received back ground meal or flour, minus a percentage called the “miller’s toll.”

There are three major parts to a gristmill: the raceway, water wheel, and grinding stone.

The raceway channels the flowing water to the wheel. The water forces the wheel to tum. The turning wheel powers the grinding stones by a series of shafts and pulleys, or gears and shafts. The grinding action of the stones breaks the grain into small, usable pieces like flour, cornmeal, and grits.

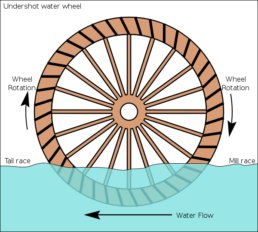

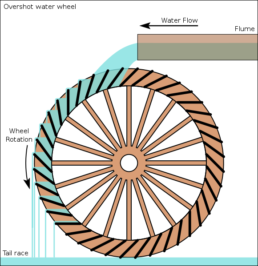

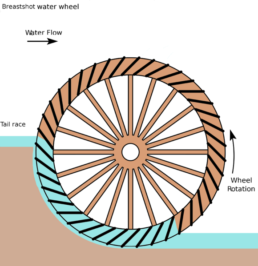

There are many types of water wheels that were used, such as an undershot wheel, an overshot wheel, or a breast wheel.

The undershot wheel was the least efficient and looked like a great paddle wheel. It was simply propelled by the flowing water pushing on its blades. Grant’s Old Mill is considered an undershot.

The overshot wheel was much more effective and took more careful planning and placement. Water was directed to the top of it, and it had blades that were more like buckets or troughs to catch and hold water. At the very least its blades were slanted rather than set perpendicular to the wheel. The weight of the water was the driving force and it built up momentum as it turned. It needed to be placed so that it was never in the stream as the motion of flowing water would slow its momentum.

Breast wheels were another type that had the water directed at about 1/2 the way towards the top of the wheel. It did better than an overshot wheel if water levels rose as it would not be drastically slowed by the water flow and was often used where it would be too difficult to use the more efficient wheel. It was halfway between the two previous types.

Want to see a water-powered grist mill in action?

Come down to Grant’s Old Mill. We’d love to show you!

If you found today’s blog post to be exactly the type of historical infotainment you were looking for, we would be very grateful

if you would help this post spread by sharing the LOVE with it socially, emailing it to a friend, or dropping us a comment with your thoughts.

We’re always interested in hearing from you and … You never know whose life you might change.

To learn more about grist mill history (1800s):

Click the button below to check out the full heritage and story of water-powered grist mills continuing from where we left off above, rolling into “Part of a Water Mill” (Sliuce gates controlling the flow of water to the wheels, etc.).

To learn about more mill history (Cuthbert Grant):

Click the button below to check out our “Infotainment” page where you can learn more about water-powered grist mills in Manitoba and a bit more history about Cuthbert Grant, as well as what else is going on at the Grant’s Old Mill.

GRATEFULLY ACCEPTING DONATIONS

Make History Long-Lasting ... Donate Today!

The Grant’s Old Mill Museum is gratefully accepting donations of money from the public and volunteer community. Allocations go to:

(1) A specific Grant’s Old Mill museum project / event;

(2) In memory of someone special in your life; and/or

(3) General revenue to keep the museum open

Please accept our heartful THANK YOU in advance for your generous gift.

We are thrilled to have your support. You truly make the difference for us, and we are extremely grateful!

Cuthbert Grant and the Battle of Seven Oaks (Victory at Frog Plain)

The Battle of Seven Oaks was a pivotal event in the history of Western Canada. It occurred on June 19, 1816, and was the result of a long-standing rivalry between the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company (NWC), two powerful fur trading companies that competed for territory and resources. The battle also involved the Métis, who allied themselves with the NWC and resisted the encroachment of the HBC and its settlers on their lands.

The conflict began in 1814, when Miles Macdonell, the governor of the Red River Colony established by Lord Selkirk, issued a proclamation that banned the export of pemmican from the colony. Pemmican was a dried meat product that was essential for the survival of the fur traders and voyageurs who traveled long distances by canoe. The NWC saw this as an attempt to starve them out of business, and the Métis saw this as a threat to their independence, livelihood, and culture. Macdonell also tried to seize pemmican supplies from NWC posts and Métis camps, which provoked violent retaliation.

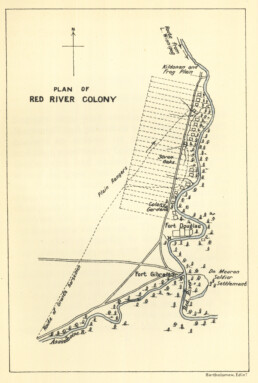

In 1816, Robert Semple replaced Macdonell as governor of the Red River Colony. He was determined to assert his authority over the region and to advance the interests of the HBC and its settlers. On June 19, he led a group of 28 men, mostly armed HBC employees, to confront a party of about 60 Métis and First Nations men, led by Cuthbert Grant, who were transporting pemmican to the NWC on Lake Winnipeg (see map for routes taken by Grant and Semple).

The encounter happened at a place called Seven Oaks, named after the oak trees that grew there, and known to the Métis as Frog Plain. A shot was fired, followed by a fierce exchange of gunfire and hand-to-hand combat. The battle lasted about 15 minutes and ended with a decisive victory for the Métis and NWC side. Governor Semple and 20 of his men were killed, while only one Métis man died, and another was wounded.

The Battle of Seven Oaks is referred to by the Métis as the Victory at Frog Plain, and it demonstrated the strength and resilience of the Métis, who asserted their rights and identity in the face of colonial oppression. The battle became a symbol of Métis pride and resistance.

If you found today’s blog post to be exactly the type of historical infotainment you were looking for, we would be very grateful

if you would help this post spread by sharing the LOVE with it socially, emailing it to a friend, or dropping us a comment with your thoughts.

We’re always interested in hearing from you and … You never know whose life you might change.

To learn more about the Métis point of view:

Click the button below to read “The Battle of Seven Oaks: A Metis Perspective” (Second Edition) from the Louis Riel Institute, by Lawrence J. Barkwell — shared with us from Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication.

To learn more about the James Reaney's translation:

Click the button below to read “The Battle of Seven Oaks: A Metis Perspective” — James Reaney’s translation of Pierre Falcon’s “The Battle of Seven Oaks” (“La Chanson de la Grenouillère”) can be found in Margaret Arnett MacLeod’s 1960 book Songs of Old Manitoba.

GRATEFULLY ACCEPTING DONATIONS

Make History Long-Lasting ... Donate Today!

The Grant’s Old Mill Museum is gratefully accepting donations of money from the public and volunteer community. Allocations go to:

(1) A specific Grant’s Old Mill museum project / event;

(2) In memory of someone special in your life; and/or

(3) General revenue to keep the museum open

Please accept our heartful THANK YOU in advance for your generous gift.

We are thrilled to have your support. You truly make the difference for us, and we are extremely grateful!